For Q3 Part e: Using a course terminology, to describe the inner function at line 4, based on when the function is invoked?

For Q3 Part h: you need to read the value from the input box

Category Archives: Uncategorized

More about SOP and CORS

The Same-Origin Policy (SOP) is a browser-enforced security mechanism that restricts how a webpage can interact with resources from a different origin. Cross-Origin Resource Sharing (CORS) is a server-configured mechanism that tells browsers which cross-origin requests are permitted. Both exist to protect users from malicious websites attempting to access sensitive data from other origins.

It’s like my office hours: I’ve decided that only CSC309 or CSC207 students can come for help.

When a polite student (like a modern browser) comes in, they tell me which course they’re from. If they’re from CSC309, I’ll help them — that’s SOP: same-origin requests just work.

If a student says they’re from another course, say CSC373, I politely tell them, “Sorry, my office hours aren’t for that course.” The polite student then leaves — that’s the browser enforcing CORS and blocking the response.

But a rude student (like Postman or cURL) can ignore my rule entirely — they can walk in pretending to be anyone. I might still help them because I can’t really verify who they are. That’s why SOP/CORS protect users only when the polite student (browser) follows the rules.

This protects the customers, because, let’s say a bank has backend API that asks for user’s login credentials, and a fake website has the same UI and prompts a user to login – obtaining their JWT, and interacting on behalf of the users – it will be very dangerous.

By the way, if you are looking at this post, please come to my office hours, attend tutorials, join the lecture discussions!

Some Context

During this week’s lecture (W8), there was one question asking whether and xmlhttprequest and fetch are both subject to SOP: meaning that an API request wont be “successful” if the request is sent to a different domain.

A more concrete example

Let’s say we have the API server running at https://sop-api.panchen.ca. Let’s talk about a GET method firs, which is using the endpoint https://sop-api.panchen.ca/api/data.

We have two frontends:

- https://sop-api.panchen.ca (Let’s call it REAL one).

- https://different-domain.panchen.ca. (Let’s call it FAKE one).

In my backend API, I do not have CORS enabled, which meant that the backend “shouldn’t” process the users’ requests. [But the fact is: the backend doesn’t really have a good way to verify which domain the user is making the request from. More details to follow]

You can open both versions to try the two APIs (one is for GET request, and the other is for POST request). If the API request is “successfully”, you will see an alert dialog.

How is the user being protected? Who’s protecting the user?

You may observe that when using the FAKE one, the requests are not successful -> by not successful we mean that the users are not getting the expected results.

But here comes a question that we did not dig into during this week’s lecture, and my wording was more or less unclear – but it’s the browser that’s protecting the users.

Why is it the browser? First thing first, the backend receives a request from the client side. But what’s inside the request can be made up – the backend does not have the authorization to check how the request is made – it can be from Chrome, can be from Postman, can also be from cURL. When we talk about security, we will be talking more about “Never trust the client“. For example, an Origin header is not like a JWT. It can be easily spoofed by modifying the header, so checking its value offers no real guarantee of authenticity. Therefore, relying on it for security is ineffective.

What the backend can do, is to take the client’s request, and check against its trusted origins. If it’s inside the trusted origins, it will include a “YES” in the response if the origin claimed by the client is inside the trusted origins.

Luckily, the modern browser will respect the information passed by the backend.

- If there’s no YES or not from the same origin, the browser won’t let the JavaScript to get access to the responses.

- If there’s YES or from the same origin, the browser will let the JavaScript to get access to the responses.

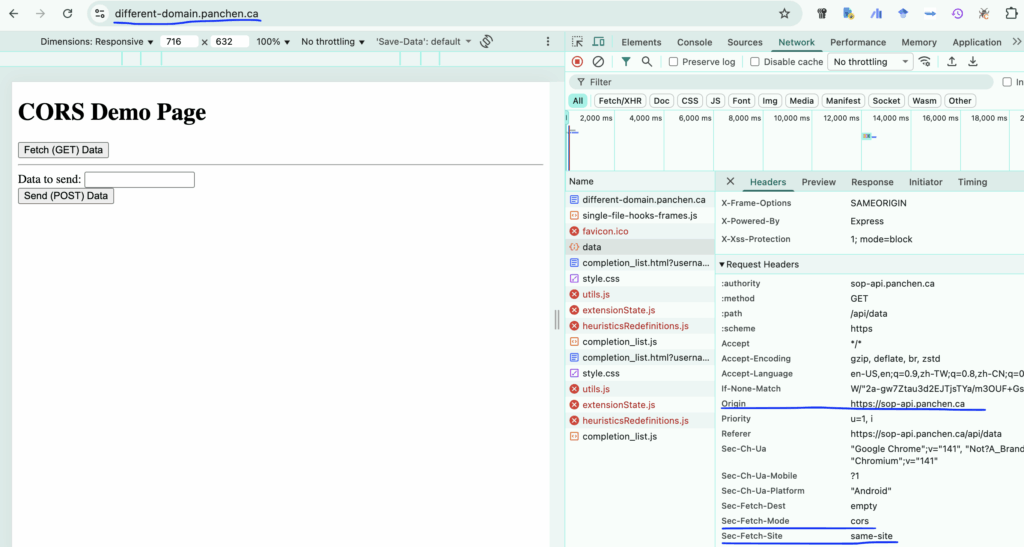

What origin does the browser specify when sending a request?

The browser automatically sets the Origin header to match the domain from which a request originates.

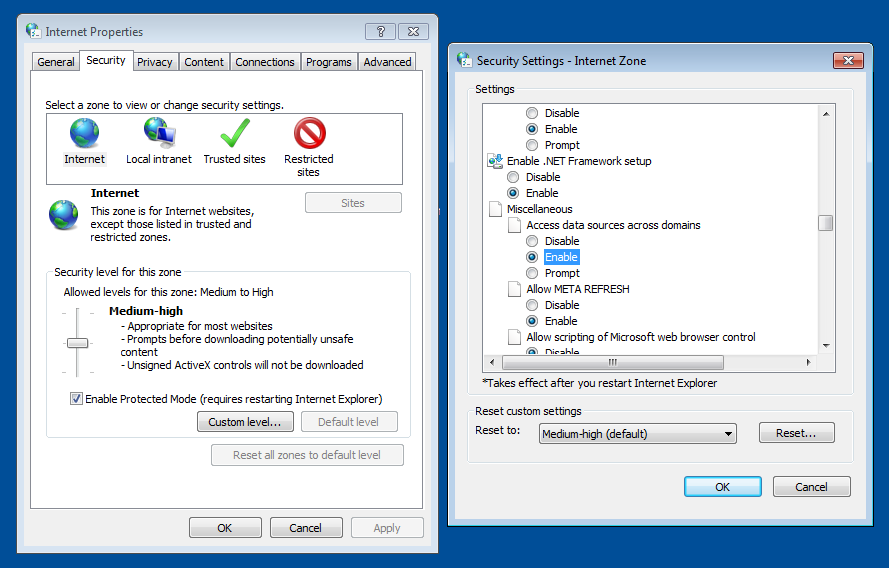

However, if a user intentionally installs a browser extension with the appropriate permissions at their own risk, they could override this behaviour and make the request claim any origin they want. This manipulation is at the user’s own risk and requires explicit action on their part.

An extension could easily make up the Origin, and makes this API request successful.

Using an old browser like Internet Explorer, one can also specify the policies in the security settings.

What about a POST method?

So, it looks like the backend will send a response for a GET request anyway, but the browser doesn’t allow the frontend JavaScript to access it if the origin is not allowed. Hence, the user won’t see the alert dialog showing GET Success.

What about a POST request? A POST method is designed to create or modify something on the backend, right? In that case, we must not allow changes if a request comes from a fake origin.

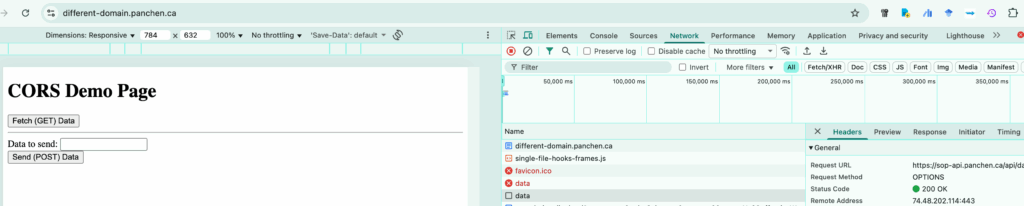

The good thing is that the browser will send a preflight request (an OPTIONS method) for cross-origin POST requests that are not “simple” and check if the origin is allowed.

It’s like the client being polite and asking the backend: “Is it okay to send this POST request from this origin?”

But again, the client doesn’t have to be polite. Tools like Postman or a custom script can send requests directly, and they can also modify the Origin header.

In my test, I tried to send a POST request from a fake origin in the browser. The browser sent a preflight OPTIONS request, the backend responded that the origin was not allowed, and as a result, the actual POST request was never sent.

The

OPTIONSHTTP method requests permitted communication options for a given URL or server. This can be used to test the allowed HTTP methods for a request, or to determine whether a request would succeed when making a CORS preflighted request. A client can specify a URL with this method, or an asterisk (*) to refer to the entire server.

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/HTTP/Reference/Methods/OPTIONS

Summary

In short, without the backend configuring CORS (i.e., specifying which domains are allowed to make requests), JavaScript running on an untrusted domain cannot perform CRUD operations on the backend. Since the request headers are constructed by the frontend, the browser is actually protecting the user — this is one of the built-in security features of modern browsers.

The backend can certainly refuse requests from untrusted websites, but as the saying goes, “locks are for honest people, not for thieves.” The purpose of CORS is mainly to protect the user, not the backend, which already has mechanisms like authentication and authorization. It therefore makes sense for the browser to handle this layer of protection.

More: CSRF (Cross-Site Request Forgery) protection

To further protect against cross-origin attacks, what the backend can do it to have a session token (CSRF token) for each session. The FAKE one doesn’t know how to make a legit token without knowing the secret.

Beyond these mechanisms, there’re more in terms of protecting the users: validating the Origin or Referrer headers, implementing rate limiting, and using secure authentication practices.

How Event Loop can get trickier

Try running the following JavaScript code in your browser, NodeJS, see what the output is. Are they consistent?

setTimeout(() => console.log("I love "), 1);

setTimeout(() => console.log("CSC309"), 0);What will browser do when there is a “conflicting” CSS rule?

During the lecture this week, we saw an edge case like the following:

Where the blue box has the following CSS properties:

left: 50px;

width: 100px;

right: 50px;The problem is: it is not possible to make the box satisfies all of the three conditions (except under some edge circumstance where the screen size happens to make it possible):

- 50px away from the left edge of its nearest positioned ancestor

- 50px away from the right edge of its nearest positioned ancestor

- Be 100px wide

So, we have to ignore one of the three properties, actually, the Browser.

There are some edge cases like this one when we deal with HTML and CSS. Sometimes we will be able to tell the answers while sometimes not. The good thing is, the behaviour is deterministic for a specific browser (or most modern browsers will share similar behaviours, as there are only three major browser engines: Blink, WebKit, and Gecko).

And we will need to refer to some official documents. Most of the time, we can find the answers from the CSS specifications from w3.org.

The problem we are talking about is one example: https://www.w3.org/TR/CSS22/visudet.html#abs-non-replaced-width. The problem we have right now is called “over-constrained”:

If none of the three is ‘auto’: If both ‘margin-left’ and ‘margin-right’ are ‘auto’, solve the equation under the extra constraint that the two margins get equal values, unless this would make them negative, in which case when direction of the containing block is ‘ltr’ (‘rtl’), set ‘margin-left’ (‘margin-right’) to zero and solve for ‘margin-right’ (‘margin-left’). If one of ‘margin-left’ or ‘margin-right’ is ‘auto’, solve the equation for that value. If the values are over-constrained, ignore the value for ‘left’ (in case the ‘direction’ property of the containing block is ‘rtl’) or ‘right’ (in case ‘direction’ is ‘ltr’) and solve for that value.

This is why the right attribute seems to be dropped.